Have your New Year’s Resolutions not panned out? Don’t know where to start or how? Need an emotional intelligence jumpstart personally or professionally?

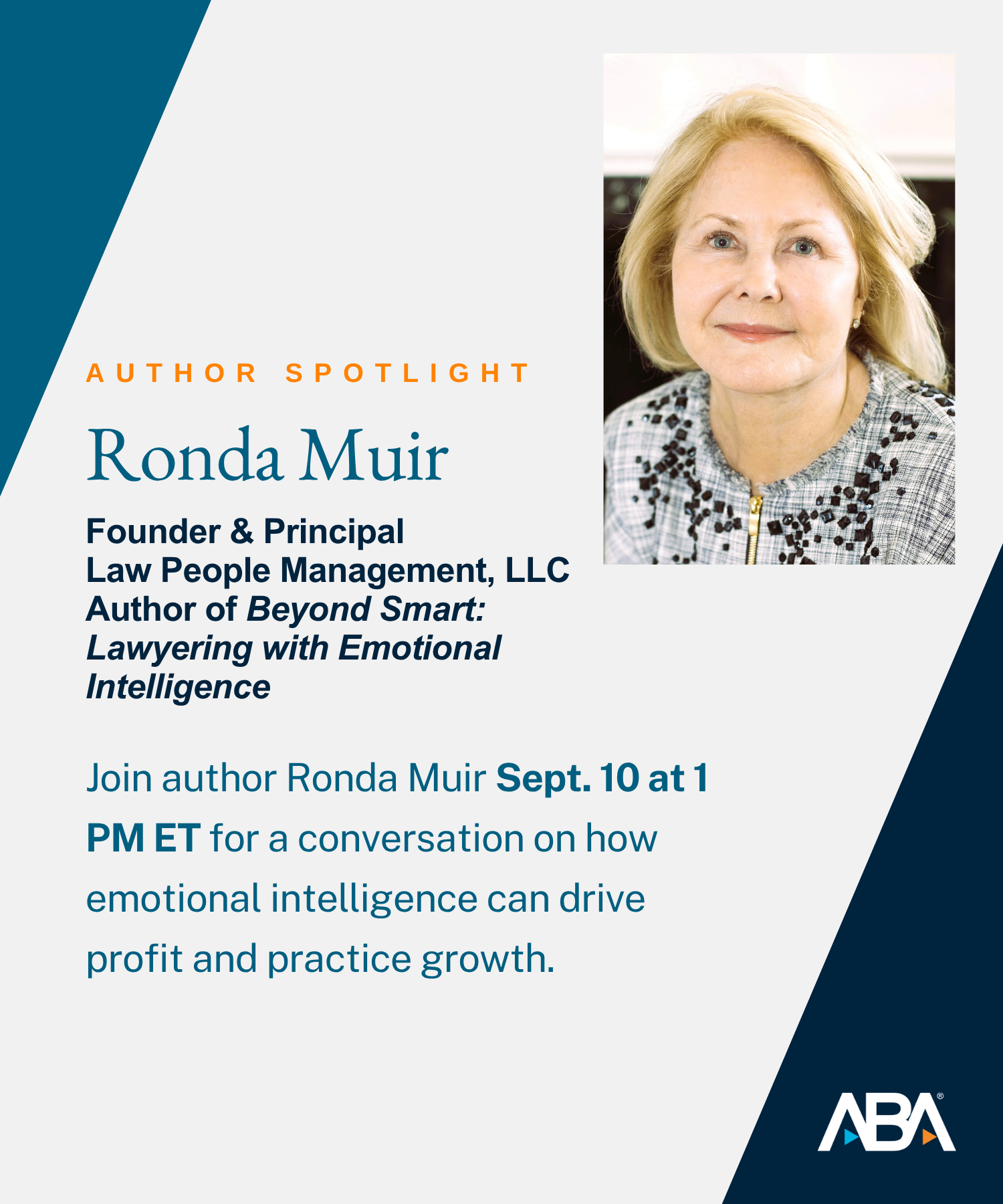

In addition to walking the walk, Ronda Muir of Law People Management is offering for a limited time personal coaching to talk the talk. The first one hour consultation is $50, and, if this is a fit, $100 for 30 minute segments after that.

Those interested should contact LPM at LawPeopleManagement01@gmail.com.

Let’s make this the best year yet!